Oral History Interview with Steffi Schwarcz

Title

Date

Contributor

Summary

Steffi Schwarcz, néeBirnbaum, was born March 17, 1928 in Berlin, Germany. She was sent to England on March 15, 1939as part of the Kindertransport, with her younger sister and 11 other children. This group was sponsored by Dr. Schlesinger, an English Jew. She briefly mentions her early life, Kristallnacht, and thegeneral atmosphere in Berlin.

Steffi describes leaving her parents and the journey to England. The children were put up in a hostel in Shepherd's Hill, Highgate. In September 1939, thechildren were evacuated and dispersed. Steffi and her sister were sent to the home of a young Christian couple in Cuffley, Middlesex. She contrasts the respectful attitude of the foster parents with the pressure to convert put on the Jewish children by the headmistress of the KingsleyBoarding School in Cornwall, run by the Church of England, where the sisters were sent in January 1940, by the Jewish Refugee Committee. A local woman intervened on behalf of Jewish children in boarding schools. She enabled them to remain Jewish, observe the Jewish holidays in her home, and to get a Jewish education. Steffi mentions that Jewish girls older than 16 were sent to the Isle of Man as enemy aliens. Steffi discusses in detail the long-term emotional effects of the Nazi era and the stay in English boarding schools on herself and her sister. She now lives in Israel with her husband and daughter.

none

More Sources Like This

of

Joseph P. O'Donnell

Joseph P. O'Donnell served with the 15th Airforce, 483rd Bomb Group, 15th Bomb Squadron, based near Foggia, Italy. He was a ball turret gunner on a B 17 and was shot down over Wienerneustadt, Austria on May 10, 1944, captured by Germans the next day, and taken to a Lager near Frankfurt/Main where he was processed. From there he was shipped by boxcar to Stalag Luft 4, a camp for about 10,000 air force enlisted men, mostly Americans, in Pomerania.

He describes conditions in the camp, which the American prisoners of war ran like a democracy. Medical care was provided mostly by fellow prisoners who were medical officers. The prisoners were able to get news from the British Broadcasting System. He never received any food packages. He witnessed no cruelty at this camp, but was told in great detail - by a soldier who survived - about atrocities committed against enlisted POW's at Stalag Luft 6.

In April 1944, the camp was evacuated. Other prisoners were dispersed throughout Germany, some by box cars, others including Mr. O'Donnell, on a 600 mile forced march, with a stopover at Stalag 11, near Fallingbostel, Germany. He was liberated by the British Second Army on May 10, 1944 in Gudow, Germany. He describes how the British processed the liberated prisoners of war and explains that he makes a distinction between the Nazis and the German people in general.

Interviewee: O'DONNELL, Joseph P. Date: March 20, 1989

of

Meyer Levin

Meyer Levin served in Europe, as a cannoneer with the 25th Tank Battalion, 14th Armored Division during World War II. About two weeks after the war ended, his tank crew was ordered to proceed to a labor camp near Munich, Germany. He never found out the name of this camp.

He relates how he disobeyed orders of an American officer during an encounter with survivors who found a warehouse full of food and clothing. He describes the pitiful condition of the surviving inmates and the reaction to and interaction with the prisoners and the American soldiers. His unit tried to help as much as they could. In Meyer's opinion, the inmates were Slavs not Jews. His unit stayed in the labor camp for less than a day but the experience lingers with him to this day and made him glad he was fighting Germans.

He was stationed in Berlin as part of the Army of Occupation and had a lot of contact with German civilians. The Germans he talked to denied the existence of the camps, even the German civilians from surrounding villages who were forced to march through the camp he liberated. He explains why he did not believe their protestations of ignorance and innocence and why he is convinced Germans and Austrians he encountered all lied about their actions during the war.

He was also involved in the repatriation of displaced persons under American control who were afraid to go home. Jewish survivors he met during High Holiday services in Austria told him that Poles were worse than the Germans.

Interviewee: LEVIN, Meyer Date: December 9, 1998

of

Harry Bass

Harry Bass was born on October 10, 1920 in Bialystok, Poland. He talks about his life, Jewish life in general, educational facilities for Jewish children in Bialystok, and his Zionist activities prior to 1939. He briefly mentions the arrival of Polish Jews who were expelled from Germany.

After the German invasion in 1939, his family hid for a while, then were forced into the Bialystok Ghetto along with the entire Jewish population of Bialystok, as well as Jews from surrounding villages and towns. He describes conditions in the ghetto, how he traded goods for food and activities of the Judenrat.

In December 1942, Harry, his three brothers, a sister and an uncle, were deported to Auschwitz in closed cattle cars. He could have escaped and explains why he chose not to.

In Birkenau, his two little brothers were sent to the crematoriums. Harry and his other siblings were taken to the slave labor camp. He describes the daily routine in the camps, living conditions, how prisoners were branded, and briefly mentions attempts at religious observance. Prisoners who tried to escape were killed. Harry worked in the kitchen, later in a Straf Kommando (punishment detail) where a German soldier saved his life.

To evacuate Auschwitz, prisoners were forced on a Death March to Gleiwitz in deep snow, then to Mauthausen on an open train on January 18, 1945. Thousands died and survivors were treated brutally. In April 1945, surviving prisoners were brought to Magdeburg and put on ships in the Elbe. Most ships were sunk by the Germans, Harry’s boat was torpedoed by the British but he managed to survive.

After liberation by the British, Harry recuperated in a hospital in Neustadt Holstein, searched for family members, and was reunited with some of them. He immigrated to the United States on March 29, 1949, where he became very involved in every aspect of the Jewish community.

The transcript includes historical endnotes by Dr. Michael Steinlauf as well as several vignettes about helping fellow prisoners, help from German soldiers and slave labor.

Interviewee: BASS, Harry Date: August 22, 1983

of

Samuel Makower

Samuel Makower, born January 6, 1922 in Przasnysz, Poland, where he attended a chederand public school. Following the German invasion of September 1, 1939, he fled with his family to Warsaw and then to Bialystok. Under the Russian occupation, they were offered contracts to work in the Ural Mountains. He describes the harsh climatic conditions and the deprivations of wartime, with mention of aid from Russian people, among whom they lived. In 1941, the family moved to Minsk and were trapped one month later when the Germans invaded and established a ghetto. He describes the killings by Germans and Ukrainians. His family survived by creating hiding places under the floor and within a false wall. A 2-year-old niece was sheltered in a Russian orphanage, with the aid of a German soldier. Dr. Makower escaped with his sister and brother-in-law to join Russian partisans who accepted Jews. He details partisan life, obtaining food and ammunition from civilians. They blew up trains and railroads and took some German soldiers as prisoners. He mentions “Uncle Vanya”, the Jewish partisan who sheltered many Jews in the forest. After liberation by the Russian Army, he helped his family who had survived move to Szczecin (Stettin). At the request of a Zionist group, he secured a train to remove 200 Jewish children to Cracow. He entered the University of Berlin and obtained a Ph.D. in chemistry and followed part of his family to Israel. Unable to find employment there, he emigrated to the United States in 1956.

Interviewee: MAKOWER, Samuel Date: August 3, 1988

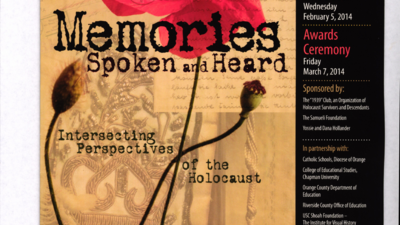

This multi-page brochure announces and provides details for the 15th Annual Holocaust Art & Writing Contest, organized by Chapman University and its affiliated centers, including the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education. The contest invites students from middle and high schools to submit original works of art, film, or writing based on Holocaust survivor testimonies. The document outlines the contest rules, submission guidelines, prizes (including a study trip to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.), and the awards ceremony scheduled for March 7, 2014. It emphasizes the theme "Memories Spoken and Heard: Intersecting Perspectives of the Holocaust," exploring how oral testimony shapes understanding and memory of the Holocaust. The background section discusses the importance of survivor testimonies, referencing the story of Oskar Schindler, Leopold and Ludmila Page, Thomas Keneally's novel 'Schindler's List', and Steven Spielberg's film adaptation as examples of how memory is transmitted and interpreted. The brochure also lists various sponsors, partners, and contributors to the event, providing contact information for inquiries and submissions.

of

Daniel Goldsmith

Daniel Goldsmith was born in Antwerp, Belgium on December 11, 1931 to Polish parents. His family was orthodox and he was educated at a Yeshiva. They lived in Antwerp under German occupation and suffered under the ever-increasing anti-Jewish measures. His father was transported to a labor camp in France, August 1942 and never heard from again.

His mother, Ruchel Goldschmidt – who was in contact with the Belgian underground – managed to get some money, safeguard their possessions, and find a hiding place just before and while the Germans raided their neighborhood and ransacked Jewish-owned houses, helped by Belgians who pointed out Jewish residents. Daniel cites several instances when Belgians cooperated with the Germans. He also gives many examples of aid by non-Jewish Belgians, especially Father André (who was recognized as a “Righteous Gentile”) and other Catholic clergy and nuns. He also mentions his mother’s work with the underground.

Daniel and his sister were placed in a convent in December 1942, then with Christian families after their mother found out the Germans were going to enter the convent to look for Jewish children. He was in a succession of orphanages in Weelde and Mechelen, run by Father Cornelissen, from 1943 to 1944, while his sister lived with another Christian family. Daniel got false baptismal papers, changed his name, lived as a Catholic, but refused to convert.

In May 1944 the Germans imprisoned all circumcised boys in the orphanage, then transported them on cattle cars with other Jewish children. Daniel and several other boys escaped from the moving train and managed to contact a priest who placed each of them with a different Christian family who hid them. Monsieur and Madame Botier, hid Daniel, were kind to him, and worked to reunite him with his mother after liberation in September 1944.

Daniel describes various placements post liberation, especially in AischeEnRefail; mentions a French committee that collected hidden Jewish children, and Aliyah Bet. His mother was injured during an air raid and could not take care of her children at that time. He relates how difficult and painful it was for all parties, especially his sister, when his mother wanted to reclaim her daughter from the Christian family that sheltered her for three years.

In April 1948, Daniel, his mother and his sister went to the United States from Belgium, sponsored by his father’s family. He talks about his family’s life shortly after they arrived, and his own life from that time to the present.