Elie Wiesel and La Nuit

Title

Date

Summary

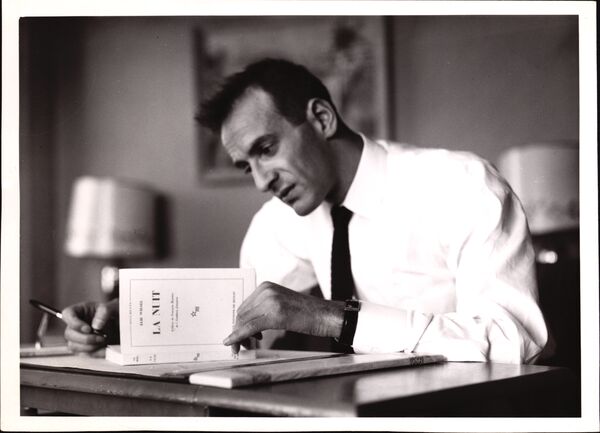

Elie Wiesel, as a young man, signs a copy of his memoir La Nuit, first published in 1958. It is a shortened French version of his Yiddish memoir, Un di velt hot geshvign (And the Word Remained Silent), published in 1955.

More Sources Like This

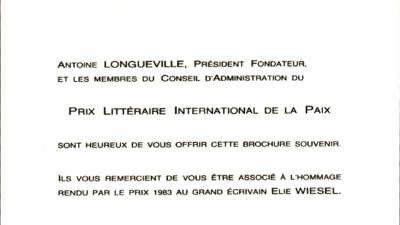

This document is a souvenir brochure from the Prix Littéraire International de la Paix (International Literary Prize for Peace). It is presented by Antoine Longueville, the Founding President, and the members of the Board of Directors. The brochure expresses gratitude to the recipient for their association with the tribute paid to the great writer Elie Wiesel by the 1983 prize.

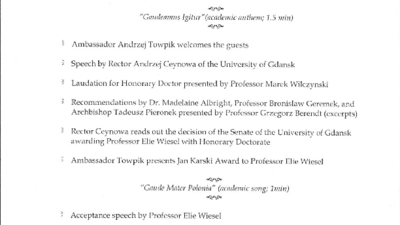

This document is a program and informational booklet for a ceremony honoring Professor Elie Wiesel. The first page outlines the program for the conferral of an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Gdańsk and the Jan Karski Award upon Wiesel. The ceremony includes speeches by Rector Andrzej Ceynowa and Ambassador Andrzej Towpik, a laudation, and an acceptance speech by Professor Wiesel. The subsequent pages provide context for the Jan Karski Award. Page two is a detailed biography of Jan Karski (1914-2000), a Polish resistance hero who reported on the Holocaust to the West. It highlights his wartime courier activities, his post-war academic career, and the establishment of the Jan Karski Society, of which Elie Wiesel was the Honorary President. Page three lists the laureates of the Jan Karski Eagle Award from 2000 to 2006, recognizing figures for humanitarian service and contributions to democracy, including Jacek Kuron, Marek Edelman, and Adam Michnik. The final page contains the formal Latin text conferring the honorary doctorate on Professor Wiesel.

of

Samuel Makower

Samuel Makower, born January 6, 1922 in Przasnysz, Poland, where he attended a chederand public school. Following the German invasion of September 1, 1939, he fled with his family to Warsaw and then to Bialystok. Under the Russian occupation, they were offered contracts to work in the Ural Mountains. He describes the harsh climatic conditions and the deprivations of wartime, with mention of aid from Russian people, among whom they lived. In 1941, the family moved to Minsk and were trapped one month later when the Germans invaded and established a ghetto. He describes the killings by Germans and Ukrainians. His family survived by creating hiding places under the floor and within a false wall. A 2-year-old niece was sheltered in a Russian orphanage, with the aid of a German soldier. Dr. Makower escaped with his sister and brother-in-law to join Russian partisans who accepted Jews. He details partisan life, obtaining food and ammunition from civilians. They blew up trains and railroads and took some German soldiers as prisoners. He mentions “Uncle Vanya”, the Jewish partisan who sheltered many Jews in the forest. After liberation by the Russian Army, he helped his family who had survived move to Szczecin (Stettin). At the request of a Zionist group, he secured a train to remove 200 Jewish children to Cracow. He entered the University of Berlin and obtained a Ph.D. in chemistry and followed part of his family to Israel. Unable to find employment there, he emigrated to the United States in 1956.

Interviewee: MAKOWER, Samuel Date: August 3, 1988

of

Andrzej W. Jurkiewicz

Andrzej W. Jurkiewicz was born into a Christian family in 1931 in Torun, Poland. His family moved to Warsaw in 1934. His father, a band leader, played for German and Soviet soldiers and was a commander in ArmíaKrajowa, the Polish home army. Andrzej was a messenger, carrying information to underground units.

His father had been helped by Jews when he served in the Polish Army during World War I and during German bombardments in 1940. Later, Andrzej and his family aided Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto, throwing food over the walls, giving bread and sheltering children who escaped the ghetto in the top of their apartment building. Andrzej witnessed the burning of the Warsaw Ghetto and machine gun killings in the streets.

In his testimony, Andrzej describes the Polish underground smuggling arms into the Warsaw Ghetto. He describes that some arms were obtained from Hungarian soldiers who were fighting with the Nazis and stationed in Warsaw. He related an incident in which a truckload of machine guns was given to the underground and he and other children helped to empty the truck and hide the guns.

In 1944, Andrzej, his family and other Poles were taken to a labor camp in Vienna, to build air-raid shelters. After the war, he was a music student in Poland, graduating in 1958 and became assistant opera conductor in Wroclaw in 1959. He describes difficulties with the Polish government because his father had stayed in Vienna and it was frowned upon to have family members in the west. In 1972, when he was already the permanent Music Director, he escaped from Poland and emigrated to the United States. He joined his parents, who had arrived in Philadelphia earlier. His sister, an opera singer, remained in Poland.

of

Vera Otelsberg

Vera Otelsberg, nee Neuman, a Warsaw Ghetto survivor, was born to a wealthy family in l924 in Bielitz (Bielsko-Biala), Poland. Her father was an industrialist who owned several factories and a mill. Her mother died when she was a young child and she was brought up by a nanny. The family was not religious, attended synagogue only on High Holidays. Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, she escaped to Warsaw with her older sister, her husband and child and nanny. Her sister with family were able to buy visas to South America and left in l940 while Vera stayed in the Warsaw with her nanny and brother-in-law’s parents.

Vera explains how they were forced into the ghetto and gives a detailed description about how she was able to get money through a relative on the Aryan side of Warsaw and describes the scarcity of food, illness, forced labor and dangers of living in the Warsaw Ghetto including a time when they had to hide from German soldiers in an attic. She describes the long hours working at the Toebbens Factory, sometimes days at a time, without being allowed home. She describes several instances of help from Poles and Germans.Mr. Wagenfeld brought money into the ghetto to Vera when her relative could not get in and also arranged to help her escape from the ghetto in the summer of 1942. A non-Jewish acquaintance of hers got her an Arbeitskarte, a work card, testifying that she worked in his office.She describes in detail living on the outside on false papers, working as a maid in a German household and later, in a village, listening to the radio illegally and translating the reports into Polish for an underground paper. She also describes how her friend Steffi was assisted by a German soldier to escape the ghetto and how family friends secured false papers for her, as well as other evidence regarding the workings of procuring false papers and how one lived as a non-Jew on the outside of the Warsaw Ghetto.

Vera describes life in Sochaczew before and during the retreat of the Germans and the killing of German soldiers by the advancing Russians. When Bielitz was liberated, she returned home with help from Russian Jewish officers. Her father had perished in Lemberg, her nanny in a death camp.Eventually Vera married, had a daughter and in l957 moved to Monte Video, Uruguay.

of

Ursula M. Heisman

Ursula M. Heisman was born in Mewe, Germany (now Gniew, Poland). Ursula grew up in Berlin and was a teenager when Hitler came to power in 1933. Her father, Isidor Hirschfeld, was a physician who served as such in the German army in World War I. He received the Iron Cross. Ursula had two older brothers. Her parents were “free thinkers” and her upbringing was an assimilated upper middle class one, with little Jewish content.

While still in high school Ursula was employed as an actress and dancer in a theater company. Ursula describes the rise of Hitler and the consequences it had for her and her family. For example, she was fired from her job as a dancer and her father could no longer practice medicine. She tells how they were made to wear the yellow star and of how her father resisted wearing it. When Ursula witnessed Kristallnacht she decided that she must leave Germany. One of her brothers, a physician, had already gone to the United States. Ursula recounts the difficulties she encountered in leaving Germany. It was only to Cuba that she was able to emigrate, and she tells of arriving in Havana, with her other brother, in 1938. Ursula recounts how she got a job as a dance teacher and that she was invited to move in with her employers, who were not Jewish, who subsequently paid $1000 to the Cuban government to obtain visas for her parents. They arrived in Cuba on the ship after the St. Louis. Ursula describes life in Havana which she enjoyed very much.

In 1945 Ursula and her parents moved to the United States, joining one brother and leaving one in Cuba, who did join them at the end of the war. She tells of resuming her career as a dancer and eventually marrying and moving to Philadelphia where she decided to open a dance school. Eventually she had three schools and a ballet company called Ballet des Jeunes which engaged the top 25 students at her schools. The company danced throughout the United States and in Europe. Ursula closes her testimony recounting a trip to Berlin she and her husband took in 1969 or 1970.