Oral History Interview with Albert Ferleger

Title

Date

Contributor

Summary

Albert (Abraham) Ferleger was born in Chmielnik, Poland, June 15, 1919. He was one of six children from a very Orthodox family and had a public school as well as a yeshiva education. He describes the customs of the Jewish Kehillahin histown, relates the Polish antisemitism before the war and describes what occurred after the Germans took over the town. He describes the influx of populations from several different towns being forced into their ghetto and describes atrocities (people being killed on the spot and burying them) and deportations. Albert was sent tozwangsarbeit, forced labor, where he shoveled snow and worked in the ghetto community kitchen.

Albert fled from the Germans and was hidden by a Polish farmer for two years: he was buried in a hole, naked, under the farmers stable, along with another Jewish man. They subsisted on bread and potatoes. He details their horrid conditions.

With the Russian victory and the help of the Briha1 (underground Zionist organization helping Jews get to Palestine) he became the leader of a group of Jews that was smuggled across the Polish and Czechoslovakian borders to Germany pretending to be Greek and later as German Jews.

He met his wife (who was liberated from Theresienstadt) through the Briha, as well. They were sent to Munich and then to a displaced persons camp in Regensdorf, Germany for seven months. With the help of HIAS and President Truman’s aid to refugees they went to relatives in Philadelphia. He relates in great detail how he was able to survive during and after the war, how his experiences challenged his religious beliefs and his bitterness that not more was not done to help the Jews.

not to be used for profit for individual or organization

More Sources Like This

of

Adele Wertheimer

Adele Wertheimer, nee Rozenel, the eldest of eight children, was born February 5, l922 in Bendzin(also Będzin),Poland to a religious family. Her parents were merchants. She gives a detailed description of pre-war Bendzin, Zionist organizations, her attendance at a Bet Yaakov school2 and her family. She describes the effect of the German invasion on their town, the rounding up of men, the curfew, the violence against women and having to wear a star. She mentions the rape of her aunt by German soldiers. She gives a detailed explanation about how the Jews were forced into the ghetto gradually and describes how they would hide from the Germans in different bunkers during round ups. She recalls when her mother and other siblings were taken away in a roundup, and she and her father and some other relatives hid in a bunker where they stayed for six weeks. They were caught and were forced to clean up the town.

Adele describes her deportation to Auschwitz in 1943, the separation from her father, her work in an ammunition factory and that she met an aunt and uncle in Auschwitz. She recalls the shared pair of shoes given to her by her aunt that she and a friend used on the death march to Ravensbrück which helped them stay alive. She describes her short stay in Ravensbrück and subsequent deportation on cattle trains to Malchoff in Germany. She shares the vignette of bribing someone with bread to get vegetables to feed a friend who had typhus and thus saved her life. She details their deportation to Taucha, a subcamp of Buchenwald/Dora-Mittelbau near Leipzig and how the Germans left all the prisoners in the open cattle cars during the Allied bombing raid to kill them. Her car miraculously survived and they were then marched on to Nossen near Freiberg. She describes walking out to a German home to get food and receiving a beating when she got back. Shortly after, she and her friend decided to escape the death march. She details their escape to a town where the Soviets were approaching and how they obtained food and clothes there and ended up going back toward Katowice with the Soviets. After the war Adele emigrated to Israel and later to the United States in 19583. She was the only survivor of her family.

of

Bess Freilich

Bess Freilich, née BashaAnusz, born in1928 in Pruzany, Poland, was the eldest of eight children in a religious Jewish family. Her father was a poor butcher, but she attended private Hebrew school. Her family lived in harmony with Polish neighbors (to whom her grandfather lent money with little or no return).

In 1939 under anti-Zionist Russian occupation, her Hebrew school was closed and teachers were sent to Siberia. Fearful of arrest, Bess burned her Hebrew books and then went to a public Jewish school where a communist curriculum was taught in Yiddish.

When the Germans invaded in June, 1941, the local population swelled from 3000 to 15,000 as Jews were brought from other towns to the Pruzany Ghetto. Food shortage was acute, and Bess often slipped through the ghetto walls to trade clothing for potatoes or steal potato peels from a German kitchen. She describes in detail the ghetto evacuation, when her grandfather was shot before her eyes, in January 1943.

Bess describes in detail the three day train trip in cattle cars to Auschwitz, arrival, brutality of the guards, and atrocities committed there including her six-year old brother’s murder for picking up snow for their mother to eat. Bess saw her mother fall from a blow to her head and later learned that she was burned in an open pit. Her older brother and father were sent to work in a crematorium as Sonderkommandos.

Bess was sent to Birkenau and then to Budy, a camp she describes as hell, where about 400 girls, ages 14 - 25, pushed heavy wagons uphill to build an artificial mountain. Some were forced to strip, dance and sing and then were shot. Some were eaten by dogs. She vividly describes suffering from typhus and lice infestation of a breast wound from beatings. Left unconscious in a morgue, she was returned to Birkenau, where she was saved from death several times, twice by German guards.

After passing three Mengele selections and seeing her father briefly in the men’s camp in Auschwitz where she worked picking weeds for soup, she was evacuated on a death march, January 18, 1945. She recalls thousands left dead in the snow before they reached Ravensbrück. They were then left in the woods near Malchow. At liberation, she weighed 67 pounds and could not retain food eaten for months afterwards.

Returning to her home town, she was taken by the Russians to a camp and questioned as a suspected German spy. Finding nothing of her home in Pruzany and threatened with transfer to Siberia, she fled to Lodz where she met and married another survivor. She found her father in Munich, spent two years in Feldafing DP camp and came to the United States in 1949.

She was unable to speak about her holocaust experience until the time of her interview in 1981.

of

Jenny Isakson Sommer

Jenny Sommer describes her life, education, and Zionist activities in prewar Libau, Latvia in great detail, including some incidents of antisemitism and discrimination. In 1940 conditions for Jews started to get worse. Because her family was upper middle class they lived in fear of the NKVD (Soviet Secret Police) and the Russians.

Jenny describes life under the German occupation of Libau in great detail: the execution of all able bodied Jewish men on July 22, 1941; a mass execution of Jews, including her relatives, and how her sister managed to rescue them just before they were to be executed during an Aktion. She witnessed a mass execution of Jews, including her relatives. The Christian superintendent of her uncle’s house hid Jenny and her remaining family in the attic until the round-up of Jews was over. Jenny, her mother and her sister, moved into the ghetto with about 600 other Jews and worked for the Germans as slave laborers. Her sister worked as a nurse in the ghetto. Some Christian Latvians smuggled food to them.

On Yom Kippur night they were taken to Kaiserwald concentration camp, near Riga. Jenny describes their arrival at Kaiserwald, where mothers were forcibly separated from their children. Some women committed suicide. Her sister carried a bottle of cyanide pills. While in Kaiserwald, Jenny did hard labor as part of a Kommando, at a work camp, and later inStutthof. She describes their horrible existence in Stutthof and how she managed to find the will to survive. Her husband worked at Stutthof as an electrician and managed to survive a typhoid epidemic.

As the Russian army approached, the inmates were shipped out of Stutthof on a designated typhoid boat. It was bombed, set on fire and capsized. She was rescued by a German fire boat after ten days without food or water, liberated two days later in Kiel, Germany by English forces. She stayed at a field Lazarett (hospital) in Itzehoe, near Hamburg for six months. She talks about her post-liberation experiences in a German hospital, and finding her husband in Neustadt.

of

Rose Fine

Rose Fine, nee Hollendar, was born in Ozorkow, Poland in 1917 to an Orthodox Jewish family. Her father was a shochet. She briefly describes living conditions during the German occupation before and after the establishment of the Ozorkow Ghetto in 1941: health conditions, deportations, and her work in the ghetto hospital where children were put to starve to death. She refers to the behavior of the Volksdeutsche in Ozorkow and her mother’s deportation to Chelmno where she was gassed to death. She witnessed the old and infirm deported in chloroform-filled Panzer trucks in March 1941 as well as the public hanging of 10 Jews. She was transferred to the Lodz Ghetto in 1942 where she worked for Mrs. Rumkowski until she was deported to Auschwitz in August 1944. After one week, following a selection by Dr. Mengele, she was transferred to the Freiberg, Germany air plane factory and later to Mauthausen in Austria, where she was liberated by the Americans in Spring 1945. She describes the birth of a baby girl (both mother and baby survived) just prior to liberation and help by a German farmer.

After liberation Rose stayed briefly in Lodz and Gdansk. She describes life in Gdansk where she got married. She and her husband lived in Munich, Germany for four years where they belonged to Rabbi Leizerowski’s1 synagogue and she attended the ORT school. She and her husband emigrated to the USA in 1949 with the help of the Joint Distribution Committee. She recounts the story of the hiding of a Torah by a non-Jew of Ozorkow and his giving it to a survivor from Ozorkow to take to Atlanta, Georgia.

See the May 4, 1981interview with Rabbi Baruch Leizerowski.

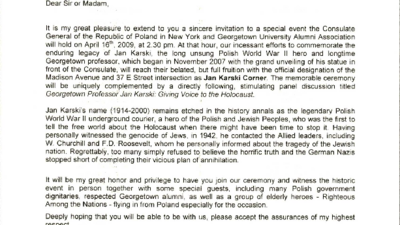

This document is an invitation from Krzysztof W. Kasprzyk, Consul General of the Republic of Poland in New York, for a special event co-hosted with the Georgetown University Alumni Association on April 16, 2009. The event aims to commemorate Jan Karski, a Polish World War II hero and Georgetown professor, known for being the first to inform Allied leaders about the Holocaust. The commemoration includes the official designation of the Madison Avenue and 37 E Street intersection as 'Jan Karski Corner' and a panel discussion titled 'Georgetown Professor Jan Karski: Giving Voice to the Holocaust.' The invitation highlights Karski's role as an underground courier who witnessed the genocide of Jews and informed W. Churchill and F.D. Roosevelt in 1942. It anticipates the presence of Polish government dignitaries, Georgetown alumni, and 'Righteous Among the Nations' from Poland.

of

Philip G. Solomon

Philip G. Solomon served in the United States Army, in the 101st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron Mechanized, which liberated the Landsberg concentration camp on April 28, 1945. He describes his unit’s arrival in Germany in February/March 1945, emphasizing their military mission and their lack of knowledge of concentration camps or the scale of mass murder. His first indication of Nazi horrors occurred after crossing the Rhine, heading east, when his unit captured small towns, liberating displaced persons from forced labor camps (mostly Eastern Europeans). His second indication came when liberating several prisoner of war camps. He details the ominous experience of finding sealed railroad cars on a siding filled with dead concentration camp victims. On April 28, 1945, his unit stopped near the city Landsberg, waiting for a bridge to be repaired and unaware of the camp 1000 yards away. A shift in the wind eventually alerted them to the smell, and sight of smoke from the camp where retreating S.S. had just massacred the inmates. The unit found about 20 starving and ill survivors. He details the conditions of the camp and his feelings upon seeing the massive piles of bodies, hangings and other atrocities. The unit had no food or medical supplies and could only radio for help. They were commanded to leave Landsberg after 20 minutes in order to seize and hold a causeway near Munich.

He describes in detail the reactions of prisoners to liberation, the response of the young soldiers to the dual experience of witnessing the atrocities in the midst of war, and his own complex and gradually evolving psychological reaction to this experience. He stresses his concern about ongoing genocides since World War II. And he affirms his faith and pride in his Jewish heritage.