Oral History Interview with Ernst L. Presseisen

Title

Date

Contributor

Summary

Ernst Presseisen was born July 13, 1928 in Rotterdam, Netherlands. His father was a businessman. He describes the German invasion of Holland and the bombing of Rotterdam in May1940. He details the gradually tightening restrictions imposed by the Germans to isolate the Dutch-Jewish citizens. After roundups of Jewish men started in July 1942, his father - helped by Christian friends who had contact with the underground - planned the family’s escape. His mother’s arrest by Dutch police aborted this plan. The entire family, including his mother, was deported to Westerbork in August 1942 and stayed there until February 1944. He describes life in Westerbork in detail, including his own development of survival skills and how his family managed to remain there instead of being deported to Poland. He briefly mentions Geneker, the commander of Westerbork.

In February 1944 he was deported to Bergen-Belsen with his family. He describes his experiences there in detail, including slave labor assignments and general deterioration of the inmates’ health. Jewish prisoners organized a theatre group “Cabaret Westerbork” in that camp. In the fall of 1944 Ernst got typhus and his oldest brother died of it. He mentions Greek Kapos. At the approach of the British Army, the Germans decided to evacuate the camp in April, 1945. Prisoners who survived the evacuation were liberated by the Russians and ordered to requisition housing in Trebitsch, Germany. Ernst briefly describes survival in Trebitsch. After his parents died of typhus, he was repatriated to the Netherlands by the Red Cross in June 1945. He talks about life in post-war Holland. He emigratedto the United States in October 1946. He settled in California with relatives and taught German history at the university level after getting his degree.

Interviewee: Ernst Leopold Presseisen Date: April 22, 1983

none

More Sources Like This

of

Elizabeth Geggel

Elizabeth Geggel1, nee Gutmann, was born on August 2, 1921 in Nuremberg, Germany. She was the older of two daughters born to Heinrich and Marie Guttman. She recalls a happy childhood. Thefamily belonged to a liberal synagogue and observed Jewish holidays. Elizabeth’s father a successful merchant, uneasy about the rise of antisemitism expanded the Swiss branch of his business. In 1931 the family left Germany and moved to St. Gallen, Switzerland. Elizabeth details her extended families’ experiences when Hitler came to power in 1933 (some of her uncles and their families moved to Italy and another unclewas sent to Dachau after Kristallnacht,but her father was able to secure his release.)

Elizabeth’s family became Swiss citizens. She relates that there were few Jews in St. Gallen,but she was active in Swiss and Jewish youth groups: scouts and Habonim. In 1939, when her parents decided to immigrate to the United States, they sent her to Englandto learn English and nursing. Her father took ill and she returned to Switzerland where she worked in a Jewish children’s home. He died in December 1939 but she, her mother and sister did come to the United States.

Mrs. Geggel discusses Mr. Sally Mayer, a Swiss businessman who lived in St. Gallen. Somewhat controversial, he was the head of the Jewish community in Switzerland and represented the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee from 1940 to 1945. Mayer was involved in a number of schemes to free Jews from concentration camps. Elizabeth looked on him very favorably and thought him very brave to negotiate face to face with Nazis as he did. She relates her mother’s request to Mayer to get an aunt out of Germany (which was successful) and reads a letter from her father-in-law, David Geggel, sent to the Swiss government thanking them for the hospitality extended to him in 1938 when he stayed in Switzerland for a short time until he could go to the United States. Shedescribes the Swiss refugee campswhich housed Austrian refugees until they could get visas to go elsewhere. Elizabeth remembers that the Swiss Jewish community, herself included, helped them with meals and other services. She believes that the Swiss government was also involved in the effort.

Even though they were in Switzerland, Mrs. Geggel recalls that they still felt at risk, especially with the early successes Germany achieved at the start of the war. Her family left Switzerland in 1941, went to Cuba for a short time and finally emigrated to the United States in January 1942.

Nickname: Lisa.

of

Victor Cooper

Victor Cooper2 was born December 26, 1914 in Strzemieszyce, Poland, the youngest of four brothers. He was married and had a six-month old son when he was drafted into the Polish Army in 1939. His wife, son and all of his family perished during the war years.

Victor describes how he was captured by Germans in 1940and was segregated from non-Jewish POWs at Majdanek death camp in Lublin. He escaped with the help of a fellow Jewish prisoner, and fled back home where he was in Strzemieszyce Ghetto for a short time,subjected to forced labor and witnessed the liquidation of the ghetto and German atrocities. He was then deported to 10 labor and concentration camps, including Będzin, Markstadt, Gross Rosen, Flossenbürgand Buchenwald. He vividly describes his experiences, conditions, backbreaking cement work and digging tunnels and how he fought to stay alive. He details a month-long death march from Buchenwald to Dachau in April 1945, during which he escaped and was recaptured several times.

In May, 1945, he was found hiding in Bavarian woods by a Jewish doctor serving with the American 7th Army. He was taken, disoriented and ill, to a Catholic hospital in Straubing. After his recovery, he worked with an American lawyer, helping to regain possession of Jewish property in the area. In June 1949, he emigrated to the United States under the displaced persons quota. He held many jobs with the United Service for Young and New Americans and several trade unions. He remarried and fathered two children. His daughter became a lawyer and his son is a professor at Columbia University.

Former last name was Kupfer.

This was recorded at the 1985 American Gathering of Holocaust Survivors in Philadelphia, Pa.

of

Myer Adler

Myer Adler was born September 2, 1914 in Rudnik, Austria, which became part of Poland after World War I. He gives a vivid description of his pre-war life. From age 14 to 21 he attended several yeshivot in nearby small towns and developed his artistic talent along with religious studies. Gradually he became less religiously observant. In 1938 he worked as a bookkeeper in Krakow after graduation from a private business school. After the German invasion, September 1, 1939 he returned to Rudnik to be with his mother. He witnessed organized and individual brutality by German soldiers and Polish civilians against Jews. Shortly thereafter, Germans forced Myer and other surviving Jews across the San River to Ulanow in Russian territory. He mentions formation of a Jewish militia to protect Jews from local Poles. Local Jews helped the refugees.

Myer spent the next six years in Russia and describes his experiences in great detail. He lived in Grodek until summer of 1940, hiding in the woods with other young men to avoid being sent to the coal mines. After he gave himself up he was deported to Siberia with his family and others who refused Russian citizenship. He lived in Sinuga and Bodaybo (Siberian villages) until 1944, when he was shipped to the territory of Engelstown to work in a government owned farm (sovkhoz).

A detailed picture emerges of his coping skills in various jobs: laborer, stevedore and farm worker, as well as descriptions of living conditions, black markets, relations with Russian bureaucrats, behavior of Russian exiles towards Jews, and attempts to practice the Jewish religion. He married in September 1945. He was repatriated in Poland in April 1946, and he and his wife went to Krakow. He mentions continued antisemitism and violence by local Poles, and help from the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC).

In August 1946 Myer and his pregnant wife were smuggled into Czechoslovakia, through Austria and to a transit camp in Vienna, helped by the Haganah, then to Germany. He gives an extensive description of life in the displaced persons camp in Ulm Germany where he stayed for 3 years, supported by UNRRA (United Nations Relief Rehabilitation Association). He mentions Bleidorn a displaced persons camp for children, also in Ulm, where he located his niece and two nephews. Myer, his wife and two sons emigrated from Czechoslovakia to the United States in 1949. There are several touching vignettes of his early life in the United States. He describes several instances of help from Jews during his early years in Philadelphia.

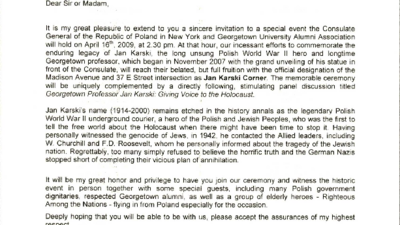

This document is an invitation from Krzysztof W. Kasprzyk, Consul General of the Republic of Poland in New York, for a special event co-hosted with the Georgetown University Alumni Association on April 16, 2009. The event aims to commemorate Jan Karski, a Polish World War II hero and Georgetown professor, known for being the first to inform Allied leaders about the Holocaust. The commemoration includes the official designation of the Madison Avenue and 37 E Street intersection as 'Jan Karski Corner' and a panel discussion titled 'Georgetown Professor Jan Karski: Giving Voice to the Holocaust.' The invitation highlights Karski's role as an underground courier who witnessed the genocide of Jews and informed W. Churchill and F.D. Roosevelt in 1942. It anticipates the presence of Polish government dignitaries, Georgetown alumni, and 'Righteous Among the Nations' from Poland.

of

Armand Mednick

Armand Mednick, named “Avrum” by his Yiddish-speaking parents, was born in 1933 into a close, extended family in Brussels, Belgium. He grew up as a stranger in a non-Jewish neighborhood, often taunted by anti-Semites influenced by the fascist Rex Party. At age six, he was hospitalized with tuberculosis until May 1940, when his father, an active political leftist, fled with his family to France. His father was drafted into the French Army, deserted and placed his son, renamed “Armand”, in a sanitarium at Clermont-Ferrand in the Auvergne Mountains. Armand’s father, mother and baby sister hid nearby in Volvic, where they passed as Christians. When Armand recovered, he joined his family and attended Catholic school. At home, there was some Jewish observance and Armand recalls walking for seven miles with his father to attend a clandestine seder.

Armand’s father joined the French resistance in 1944 and the family returned to Brussels in 1945, where Armand was the first Bar Mitzvah celebrant after the war. The Mednick family moved to Philadelphia in 1947. Buchenwald death lists confirmed that most of their extended family of 55 relatives had been killed. Armand became a potter and teacher and produced a series of clay reliefs with symbolic Holocaust images, in an attempt to exorcise his painful childhood memories.

See also interview with his father, Bernard S. Mednicki.

Interviewee: MEDNICK, Armand Date: June 15, 1983

of

Philip G. Solomon

Philip G. Solomon served in the United States Army, in the 101st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron Mechanized, which liberated the Landsberg concentration camp on April 28, 1945. He describes his unit’s arrival in Germany in February/March 1945, emphasizing their military mission and their lack of knowledge of concentration camps or the scale of mass murder. His first indication of Nazi horrors occurred after crossing the Rhine, heading east, when his unit captured small towns, liberating displaced persons from forced labor camps (mostly Eastern Europeans). His second indication came when liberating several prisoner of war camps. He details the ominous experience of finding sealed railroad cars on a siding filled with dead concentration camp victims. On April 28, 1945, his unit stopped near the city Landsberg, waiting for a bridge to be repaired and unaware of the camp 1000 yards away. A shift in the wind eventually alerted them to the smell, and sight of smoke from the camp where retreating S.S. had just massacred the inmates. The unit found about 20 starving and ill survivors. He details the conditions of the camp and his feelings upon seeing the massive piles of bodies, hangings and other atrocities. The unit had no food or medical supplies and could only radio for help. They were commanded to leave Landsberg after 20 minutes in order to seize and hold a causeway near Munich.

He describes in detail the reactions of prisoners to liberation, the response of the young soldiers to the dual experience of witnessing the atrocities in the midst of war, and his own complex and gradually evolving psychological reaction to this experience. He stresses his concern about ongoing genocides since World War II. And he affirms his faith and pride in his Jewish heritage.