Oral History Interview with Werner Glass

Title

Date

Contributor

Summary

Werner Glass, born in 1927, the youngest child of a Berlin pediatrician, emigrated to Shanghai in 1933 with his family and governess. His father, a founder of the Shanghai Doctors Association, practiced medicine in the family’s apartment in the International Settlement. A comfortable life, with many Chinese servants, is described. Werner attended German and English schools, technical college and a French-Jewish university. A vignette relates student resistance to Japanese occupation.

In 1938, his father’s passport was not renewed and the family became stateless. An influx of German refugees, including his grandparents, led to the formation of the JüdischeGemeinde; he details refugee support by the “Joint” and the Sephardic community. He describes his religious education, his Bar Mitzvah in 1940, and his activity in a Jewish Boy Scout troop.

After Pearl Harbor, enemy nationals were interned in a Japanese POW camp, and a ghetto was established in Hongkew for all post-1937 refugees, both Jews and non-Jews. The Glass family, as stateless immigrants who arrived in 1933, were unaffected. In 1942, they were dispossessed by a Japanese officer and moved into one room in a hotel occupied by Chinese and Russian prostitutes. Difficult living conditions, Japanese rules of conduct and penalties for infractions are depicted.

Werner emigrated to the United States in 1947, sponsored by his sister Helga who married an American-Jewish soldier. He completed graduate studies in Chemical Engineering at Syracuse University, married and fathered several sons.

More Sources Like This

of

Erna Schindler

Erna Schindler, nee Lowenthal, was born in Munich in approximately 1919. Her mother died when Erna was 10 years old, she was raised by her father. He had a business selling farms and farm equipment. Erna describesnever having experienced antisemitism until Hitler came to power. She and other Jewish students then had to leave their private, non-denominational school. Thereafter in Germany, she always lived in fear. For a few years, she worked for a Jewish newspaper, theBayrischeJüdischezeitungand she was told stories about how in 1933 the Germans had come in and damaged all the printing machines.

In 1938, Ernaemigrated to the United states and married a German Jew who had preceded her and became her sponsor. She was befriended by a gentile friend who signed her emigration papers. Erna explains how her father was hidden in Germany for two years by a non-Jewish friend, but then gave himself up for fear of his friend and friend’s family being punished. He was also helped by a non-Jewish, youngfriend during his confinement in Theresienstadt, 1942 – 1945, and after the war until his death. Erna visited this friend in Germany in the 1960s and learned of her father’s experiences.

of

Rose Fine

Rose Fine, nee Hollendar, was born in Ozorkow, Poland in 1917 to an Orthodox Jewish family. Her father was a shochet. She briefly describes living conditions during the German occupation before and after the establishment of the Ozorkow Ghetto in 1941: health conditions, deportations, and her work in the ghetto hospital where children were put to starve to death. She refers to the behavior of the Volksdeutsche in Ozorkow and her mother’s deportation to Chelmno where she was gassed to death. She witnessed the old and infirm deported in chloroform-filled Panzer trucks in March 1941 as well as the public hanging of 10 Jews. She was transferred to the Lodz Ghetto in 1942 where she worked for Mrs. Rumkowski until she was deported to Auschwitz in August 1944. After one week, following a selection by Dr. Mengele, she was transferred to the Freiberg, Germany air plane factory and later to Mauthausen in Austria, where she was liberated by the Americans in Spring 1945. She describes the birth of a baby girl (both mother and baby survived) just prior to liberation and help by a German farmer.

After liberation Rose stayed briefly in Lodz and Gdansk. She describes life in Gdansk where she got married. She and her husband lived in Munich, Germany for four years where they belonged to Rabbi Leizerowski’s1 synagogue and she attended the ORT school. She and her husband emigrated to the USA in 1949 with the help of the Joint Distribution Committee. She recounts the story of the hiding of a Torah by a non-Jew of Ozorkow and his giving it to a survivor from Ozorkow to take to Atlanta, Georgia.

See the May 4, 1981interview with Rabbi Baruch Leizerowski.

of

Lillian Wishnefsky

Lillian Wishnefsky, née Kupferberg, was born in Sosnowiec, Poland in December 1929. Her father was a merchant and her mother a professional pianist. Her family observed the Jewish holidays. She attended public school until fourth grade when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. She describes the formation of the Sosnowiec Ghetto in 1941, the confiscation of her father’s factory, her clandestine education, life in the ghetto, her family’s move to the Srodula Ghetto; her mother obtained false papers and was hidden by Christians. She describes the Nazis taking her father in the middle of the night, murdering her grandparents and deporting her to a camp and later Auschwitz.

Even though she was only 12 ½ years old, she was not sent to the children’s camp in Auschwitz but was instead assigned to forced labor. Her barracks were across the street from the gas chambers. One and a half years later she was sent on the death march to Ravensbrück. She was part of a prisoner exchange arranged by President Roosevelt and traveled to Sweden via Denmark. She describes her experience on a Swedish farm and her move to Stockholm which was precipitated by a Swedish publishing company’s interest in her diary. She moved to the United States in November 1545.

of

Marian Filar

Born December 17, 1917 in Warsaw, Poland, Marian Filar was a member of a musical and religious Jewish family who became a child prodigy and a noted concert pianist and teacher. His father was a manufacturer and his grandfather was a rabbi. He studied at the Warsaw and Lemberg conservatories and graduated from Gymnasium in Warsaw. In September, 1939, he fled to Lemberg following the German invasion. After graduation from the Lemberg Conservatory in December, 1941, he rejoined his family in the Warsaw Ghetto. He worked with a labor group taken outside the ghetto to a railroad workplace in Warsaw West. He describes severe beatings by S.S. guards and his rescue by a Polish railway man. He details his solo performance and other symphony concerts in the ghetto by Jewish musicians, often playing music by forbidden composers. He mentions ghetto deportations, 1942-43, when his parents and siblings were taken.

In May, 1943, after the ghetto uprising, he was deported to Majdanek. After beatings and near-starvation, he volunteered for a labor camp in Skarzysko-Kamiena, where he received aid from a fellow worker who was Polish. Moved to Buchenwald in August 1944, he was housed in a tent camp with Leon Blum, Deladier and other prominent politicians and clerics. Mr. Filar was moved next, by train, to Schlieben, near Leipzig, to work in a bazooka factory, where a Polish kitchen maid gave him extra food. His piano playing impressed the German civilian camp supervisor who transferred him to an easy job to protect his hands. As the war front moved near, he was sent with other prisoners by train to Bautzen and then on a death march to Nicksdorf (Mikulasovice) in Czechoslovakia. He and two brothers survived and lived in Zeilsheim Displaced Person’s camp in Germany for two and a half years.

After liberation, he performed in concerts through Western Europe and toured Israel, playing with the Israeli Philharmonic during the war in 1956. He shares a moving vignette about going to Professor Walter Gieseking’s villa and auditioning to become his student. He studied with him for five years.He emigrated to the USA in 1950, where he played with many American orchestras, headed the piano department at Settlement Music School in Philadelphia, and joined the faculty at Temple University. After retirement, he taught privately and judged international piano competitions.

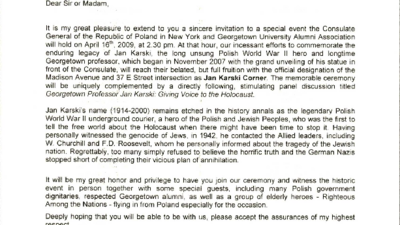

This document is an invitation from Krzysztof W. Kasprzyk, Consul General of the Republic of Poland in New York, for a special event co-hosted with the Georgetown University Alumni Association on April 16, 2009. The event aims to commemorate Jan Karski, a Polish World War II hero and Georgetown professor, known for being the first to inform Allied leaders about the Holocaust. The commemoration includes the official designation of the Madison Avenue and 37 E Street intersection as 'Jan Karski Corner' and a panel discussion titled 'Georgetown Professor Jan Karski: Giving Voice to the Holocaust.' The invitation highlights Karski's role as an underground courier who witnessed the genocide of Jews and informed W. Churchill and F.D. Roosevelt in 1942. It anticipates the presence of Polish government dignitaries, Georgetown alumni, and 'Righteous Among the Nations' from Poland.

of

Sophie Roth

Sophie Roth, née Parille, born in Zloczow, Poland, was one of four children in a religious family. She refers to the German bombing and invasion in 1939, and the killing of doctors and teachers by Germans, aided by Poles and Ukranians. She worked in forced labor camps in Lazczow and Kosice until 1942, when she was shot and lost a leg. A Polish teenager, whom she tutored, travelled to Lemberg to obtain a prosthesis for her.

She describes hiding in a fish barrel and then in a Polish peasant’s stable with her family, in exchange for money, jewelry and the deed to their house. She details near-starvation and suffocating subliminal existence under a manure pile with nine other people. Forced to leave by their sadistic “benefactor”, her family found shelter in an unheated basement of a Polish teacher, Elena Sczychovska, and her husband, who was the local police commandant. Fourteen people were sheltered there during the last year of the war. She mentions the hostility of neighbors when her family returned to their home.

In 1947, she married a Hebrew teacher who lost his religious faith and his entire family. She remained a believer, attributing her survival to God’s miracles. A daughter was born in Paris in 1952 and the family emigrated, aided by HIAS and by Jewish Family Service in Philadelphia. She reads several poems, recalling horrendous Holocaust memories, into the interview.

Interviewee: ROTH, Sophie Date: March 9, 1988