Oral History Interview with Rachel Hochhauser

Title

Date

Contributor

Summary

Rachel Hochhauser, née Swerdlin, was born July 2, 1928 in Krzywice, Poland. She was the only child of a religious family. Her grandfather was Rabbi and Shochet of the shtetl. Her grandmother and parents operated a general store. She describes religious education and a comfortable life, pre WWII, and friendly relations with Polish and Russian neighbors until September 3, 1939. She details restrictive occupations under Russians and subsequent persecution by Germans and local collaborators in summer of 1941. When her father was killed she went into hiding with her mother and other relatives after warnings from non-Jews, including the police Kommandant for whom she worked.

The family hid on several farms from April, 1942 until 1944. They were protected for 20 months by a Catholic farmer’s wife, Anna Kobinska, with whom Rachel continued to correspond after the war. When forced to move for the final time, they went into a partisan-occupied area. She describes the privations of living in a swamp during the winter of 1943-44. A log bunker built for them in the woods in exchange for 20 rubles of gold sheltered ten people until spring, 1944. The Russian Blitzkrieg and deserting Germans drove the group to return to their homes in Krzywice, where her family was welcomed home by neighbors. They adopted an orphan girl found in their house and moved westward to the DP camp at Foehrenwald. Rachel describes her education there in an ORT school. She immigrated to the United States in April, 1951.

Recorded at the 1985 American Gathering of Holocaust Survivors in Philadelphia, PA.

More Sources Like This

of

Ilsa R. Katz

Ilsa R. Katz was born December 10, 1921 in Venningen, Pfalz, Germany. Her father was a kosher butcher and a World War I veteran. She briefly describes her life and education (both secular and religious) before and after Hitler came to power including the escalating anti-Jewish restrictions and increasing antisemitism.

During Kristallnacht, November 9, 1938, their synagogue was burned and all Jewish men were arrested. A non-Jewish villager saved the Torah scroll. The next morning all Jews were rounded up and deported by bus to a meadow near Karlsruhe, Baden.

Because her father had obtained Visas, Ilsa and her family were able to leave for the United States from Hamburg, Germany to Philadelphia in December 1938. Most of her relatives were deported and killed. Ilsa talks about their life in Philadelphia, how they made a living and adjusted to life in America.

Interviewee: KATZ, Ilsa R. Date: Sept. 11, 1989

of

Moshe Moskowitz

Moshe Moskowitz was born in 1922 in Lespitz-Baya, Romania to a merchant family that was traditional but not deeply religious. He studied in a Jewish school, then in a vocational school. He planned to go to Palestine, joined a Zionist youth group and worked in an agricultural community. After the German occupation, Jews were transferred from the villages to the large cities, and many were sent to forced labor camps. His Zionist youth group became active in the resistance. Moshe took on Aryan identity, as did others who had contact with Zionist emissaries in Constantinople and Switzerland. Emissaries from England and the U.S. often attended the resistance meetings. The diplomatic courier who carried letters from the resistance betrayed them, and those who were arrested were sent to camps in Transnistria.

Moshe and his group smuggled children out of camps, gave them false identities, and set up cultural activities until they could be processed to go to Palestine on illegal immigration on ships. In 1944, British-trained parachutists from Palestine landed in Romania and Moshe’s Zionist group was among those who gave them identity papers, living quarters and maps to help them reach Bucharest. They also helped German, American and English prisoners-of- war in Brasov with money, clothing and medicine. After liberation, they rushed to the American and British zones to take Jewish prisoners out of the range of German bombings. Moshe was in charge of the funds through the Landsmanshuteyfor such operations. Groups who were involved in saving children maintained connections in Israel. Moshe emigrated to Israel post-war.

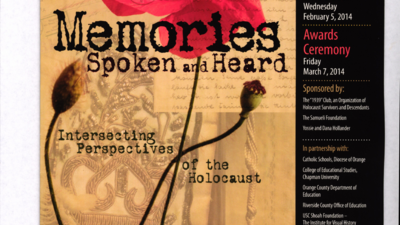

This multi-page brochure announces and provides details for the 15th Annual Holocaust Art & Writing Contest, organized by Chapman University and its affiliated centers, including the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education. The contest invites students from middle and high schools to submit original works of art, film, or writing based on Holocaust survivor testimonies. The document outlines the contest rules, submission guidelines, prizes (including a study trip to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.), and the awards ceremony scheduled for March 7, 2014. It emphasizes the theme "Memories Spoken and Heard: Intersecting Perspectives of the Holocaust," exploring how oral testimony shapes understanding and memory of the Holocaust. The background section discusses the importance of survivor testimonies, referencing the story of Oskar Schindler, Leopold and Ludmila Page, Thomas Keneally's novel 'Schindler's List', and Steven Spielberg's film adaptation as examples of how memory is transmitted and interpreted. The brochure also lists various sponsors, partners, and contributors to the event, providing contact information for inquiries and submissions.

of

William McCormick

William Mc Cormick was a sergeant in the 15th Reconnaissance Group, attached to Seventh Army Headquarters. He entered Dachau one day after the initial liberation and stayed for two days. He gives a very powerful description of the physical and mental condition of the survivors; bodies in boxcars and in piles on the ground, and human ashes in boxes near the crematorium. He reports that the Nazis killed 30,000 prisoners the week before liberation. He describes his reaction as well as that of others in his unit, and the lasting effect that what he saw in Dachau had on him.

Interviewee: MC CORMICK, William Date: January 11, 1988

of

Gerald Adler

Gerald Adler, born June 27, 1925 in Elmshorn, Germany, grew up in a middle-class Orthodox Jewish family. They moved to Berlin where he attended school until 1938. His father lost his job after Hitler came to power. Gerald talks about the effects of the Nuremberg laws on German Jews. During Kristallnacht his father was arrested and sent to Sachsenhausen. He was released after two months when his wife secured passage to Trinidad.

Gerald worked on Hakhsharah farms near Hamburg from 1939 to 1941, when he rejoined his family in Berlin. He briefly mentions an aktionin Berlin in 1942 in which all the Jews were arrested at their work places. He explains how he was allowed to go home that night for some unknown reason.

In 1943, after immigration to Trinidad was stopped, the family was deported to Theresienstadt. He credits his father’s record as a decorated World War I veteran for saving them from deportation to Poland. In August of 1943, Gerald was sent back to Wulkow, Germany in a labor detachment building barracks. He describes the increased brutality shown by the SS as the war was coming to a close and describes one incident of humanity shown to him by a lower-ranking officer when he injured his foot.

He discusses his belief in the power of prayer and tells the story of how he and several other workers tried to figure out when Rosh Hashanah would be in order to observe Yom Kippur. On the day they observed Yom Kippur, they received an astonishing and unusually large lunch, which he kept until the evening. When he returned to the barracks prisoners were checked for food, but incredibly he was skipped and enjoyed his large portion of lunch as well as a dinner they received. He returned to Theresienstadt in January 1945 where he was liberated on May 11, 1945. He emigrated to the United States May 21, 1946.

of

Miro Auferber

Miro Auferber was interviewed in Haifa, Israel in Serbical Yiddish which his interviewer translated into English. He was born in Osijek, Croatia, November 22, 1913. His father was a manufacturer and his family was active in the Jewish community and belonged to Zionist organizations. Miro was taken to forced labor, his parents perished in Auschwitz, and his pregnant wife was killed by the Ustashi. He also served as a reserve officer in the Yugoslav army in April 1941, became a prisoner of war but managed to escape.

Miro talks about his experiences, often in great detail, as a slave laborer and a prisoner, in Gospic harvesting crops, and in Jasenovac working at a steam power plant in 1941. He gives a detailed account of the detention camp were his group and Jews from Pag were imprisoned; both Jews and Serbs were brutalized and starved, as well as cruel treatment by Ustashi guards. No written records of prisoners were kept until 1942. He explains how a leather factory established by Sylvio Alkali, a Sarajevan, and Avraham Dimayo, a Jew from Belgrade, enabled the prisoners to survive. In 1942 the Ustashi liquidated thousands of Jews they brought to Jasenovac. In April 1945, the population of Jasenovac was liquidated and the buildings destroyed. Two hundred and fifty of the leather workers, including Miro, resisted, but all but eight were killed.. Miro joined the partisans, the Yugoslav People’s Army. He mentions his return to Osijek, subsequent arrest and release.

Miro talks about his feelings of shame and guilt. He again details the atrocities the Ustashi committed against Serbs and Jews. Mr. Auferber emigrated to Israel in 1948.