Oral History Interview with Genia Klapholz

Title

Date

Contributor

Summary

GeniaKlapholz, nee Flachs2, was born in 1912 in Wisnicz, near Krakow, Poland to a religious family. After the town was ghettoized, she witnessed her baby niece kicked to death by a German soldier. Genia and a younger sister escaped and paid a woman in a neighboring village who hid them for eight days. They had to return to Wisnicz and were then transported to the Bochnia Ghetto, where they worked in a uniform factory for one year, enduring terrible conditions. They moved next to the Szebnie transit camp, where they saw Jews from Tarnow burned alive. Genia reads aloud her Yiddish poem, “In Memory of My Sister, Serl, of Camp Szebnie.” (Included with the transcript are Yiddish transliteration and English translation of this poem. Also included are the Yiddish transliteration and English translation of another poem, “The Death March from Auschwitz.”)

Genia worked for three months as a cleaning woman in a factory at Szebnie before deportation to Auschwitz in 1942, which she describes in detail. She discusses the brutal treatment during her two years in Birkenau. She worked in the ammunition factory from which four youngwomen smuggled gunpowder for the attempted explosion of the crematoria and she witnessed their hanging. She describes in detail a delousing procedure, when she had to stand in the snow, naked, for hours. She also tells of her foot operation, performed without anesthesia. Forced to leave Auschwitz on a death march in January, 1945, she managed to escape with two other women and they found shelter with a Polish woman and her family in Silesia. This family was recognized as one of the “Righteous among the Nations” by YadVashem in 1991. Documentation from YadVashem accompanies the transcript.

Genia was liberated by the Russians, March 28, 1945, and returned to Krakow in search of her family. She was in Displaced Persons camps in Einring, Regensburg and Landsburg, where she met and married her cousin, Henry Klapholz. With their baby son, they immigrated in 1948 to the United States, where they bought a farm in Vineland, New Jersey. In 1955, they moved to Philadelphia.

none

More Sources Like This

of

Sally Abrams

of

Sarah Elias

Sarah Elias, nee Perl, was born in 1921 in Czechoslovakia, in what is now VelkýBočkov, Ukraine. Her father, as well as the rest of the family, was very involved in the synagogue. Her father worked in a woodworking factory and her mother and the children tended the farm and animals. There were nine children in the family. Sarah went to a Czech school. She lovingly describes the traditional Jewish observances of the family. Sarah completed high school in 1939, just around the time that their area of Czechoslovakia was annexed by Hungary. She and a group of friends then went to Budapest where she got a job working in a Jewish sanatorium for three years. When the Germans took over the facility, she went to work in a Jewish hospital. Sarah tells how, eventually, she was taken by the Germans for hard labor. In the summer of 1944, Sarah and her sister were on a forced march to Germany from which they escaped. They were helped by two strangers andthen returned to Budapest. Through a friend they were able to obtain Hungarian birth certificates and Sarah relates how they were tutored by friends, including a priest, on how to behave like Christian girls and on what they needed to know to pass as Christians. They went to a farm in the countryside but in a short time they were informed upon and were taken into custody. Sarah describes how they convinced the authorities that they were not Jewish.

When the war ended in 1945, Sarah went back to working in a hospital, where she contracted typhus and was very ill. When she recovered, she and her sister returned to their home to find her father and one brother who had survived1. Although Gentiles had moved into their home, they left when the survivors returned. Sarahmet and married Victor Elias and had a child. Sarah relates that when the Communists took over Czechoslovakia, people would disappear. Although they were doing well financially, they decided to leave for Israel where they had two more children. Sarah describes the difficult conditions in Israel, but was able to get a nice place to live and she says that they were happy there. However her husband then developed kidney disease and they came to the United States, to Philadelphia. She eventually got a job in nursing and her husband, who was not well, opened a bakery.

This interview ends rather abruptly at that point.

See also the interview with herhusbandVictorElias.

Sarah’s brother, Josef Perl survived Plaszow, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, Gross-Rosen, Bolkenhain (a subcamp of Gross-Rosen), Hirschberg and Buchenwald. His testimony can be found at the websitehttp://www.josefperl.com/josefs-story/. There is also an interesting article about him here http://45aid.org/064/.

of

Rose Fine

Rose Fine, nee Hollendar, was born in Ozorkow, Poland in 1917 to an Orthodox Jewish family. Her father was a shochet. She briefly describes living conditions during the German occupation before and after the establishment of the Ozorkow Ghetto in 1941: health conditions, deportations, and her work in the ghetto hospital where children were put to starve to death. She refers to the behavior of the Volksdeutsche in Ozorkow and her mother’s deportation to Chelmno where she was gassed to death. She witnessed the old and infirm deported in chloroform-filled Panzer trucks in March 1941 as well as the public hanging of 10 Jews. She was transferred to the Lodz Ghetto in 1942 where she worked for Mrs. Rumkowski until she was deported to Auschwitz in August 1944. After one week, following a selection by Dr. Mengele, she was transferred to the Freiberg, Germany air plane factory and later to Mauthausen in Austria, where she was liberated by the Americans in Spring 1945. She describes the birth of a baby girl (both mother and baby survived) just prior to liberation and help by a German farmer.

After liberation Rose stayed briefly in Lodz and Gdansk. She describes life in Gdansk where she got married. She and her husband lived in Munich, Germany for four years where they belonged to Rabbi Leizerowski’s1 synagogue and she attended the ORT school. She and her husband emigrated to the USA in 1949 with the help of the Joint Distribution Committee. She recounts the story of the hiding of a Torah by a non-Jew of Ozorkow and his giving it to a survivor from Ozorkow to take to Atlanta, Georgia.

See the May 4, 1981interview with Rabbi Baruch Leizerowski.

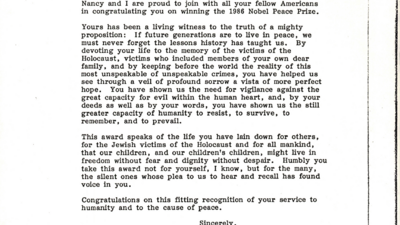

This letter, dated October 15, 1986, is from Ronald Reagan (and Nancy Reagan) to Professor Elie Wiesel, extending congratulations on his 1986 Nobel Peace Prize. Reagan emphasizes the importance of remembering historical lessons, particularly the Holocaust, to secure future peace. He praises Wiesel's life as a powerful testament to truth, recognizing his dedication to the memory of Holocaust victims, including his own family. The letter highlights Wiesel's role in demonstrating humanity's capacity to resist evil and advocate for peace, asserting that his award is a fitting acknowledgment of his profound service to humanity.

Rebecca tells her sister-in-law Maria about the reaction to Stephen Decatur Jr.'s death in a duel and about a wave of crimes and violence in Philadelphia. She also describes the achievements at the Pennsylvania Institution for the Deaf and Dumb and references the novel Ivanhoe and other recent publications.

of

Elizabeth Kemény-Fuchs

Baroness Elizabeth Kemény-Fuchs, the Austrian-born young wife of the Hungarian Foreign Minister Gábor Kemény, was shocked by the October 1944 persecutions of Jews under the Arrow Cross government. She thus, when approached by Wallenberg, was ready to help him, mainly by persuading her husband to help issue protective passports for Jews and also prevailing upon the German Ambassador Veesenmayer to issue needed visas, all at considerable risk to herself. She outlines how the stress of this, of the official duties, and of a difficult pregnancy caused her to go for a brief visit to her mother in South Tyrol, and how because of the baby’s birth and the Soviet siege of Budapest she never could return there.

She critiques a film made about Wallenberg and her role, describing his actual activities, his special qualities, and his one misjudgment, being that of the Soviets’ motivations. She mentions aid to Jews by Weiss diplomats and by Angelo Rotta, the papal nuncio. She asserts that her own involvement was solely humanitarian and that she neither is of Jewish descent nor ever was Wallenberg’s mistress. She insists that her husband was not a Nazi, that indeed he helped save many Jews, and that the unjust idea of collective guilt led to his arrest, condemnation, and execution. She describes her own post-war struggles.

She feels more could have been done, especially by Swedes, to free Wallenberg, doubted that he was still alive, asserts that he should remain “a very bright example” in an ever more selfish world.